Floppy Disk vs. Hard Disk: Why One Survived

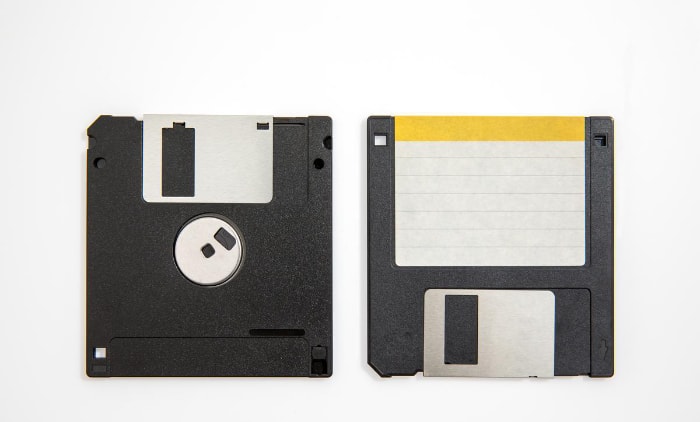

For most modern computer users, the “Save” icon is just a blue square symbol. Yet for those who grew up in the late 20th century, that icon represents a tangible object that once ruled the computing world: the floppy disk.

This humble plastic square defined portable storage for decades before fading into obsolescence, leaving behind the massive data centers and personal clouds we rely on today. While the floppy disk and the hard drive share a common ancestry rooted in magnetic physics, they sit on opposite ends of the technological spectrum.

One is defined by physical limitations and distinct portability, while the other is characterized by raw capacity and permanence.

Anatomy of a Drive

To the naked eye, storage drives often look like simple black boxes or plastic squares, but the internal architecture tells a different story of engineering priorities. The fundamental difference between a floppy disk and a hard disk lies not just in how much they hold, but in how they are built to hold it.

Their physical construction dictates their speed, durability, and how the computer interacts with the data stored inside. While both rely on magnetism to record binary code, the mechanical execution of that task varies wildly between the two formats.

Material Composition

The name “floppy” is quite literal. Inside the rectangular plastic shell of a standard 3.5-inch disk sits a thin, circular piece of plastic film.

This film is coated with a magnetic medium similar to the tape found in audio cassettes. If you were to break open the casing and hold the disk itself, it would wobble and bend easily.

This flexibility was a necessary feature for the technology of the time, allowing the read heads to press physically against the media to retrieve data without shattering the disk.

In contrast, a hard disk drive (HDD) gets its name from the rigidity of the platters inside. These platters are typically made of aluminum, glass, or ceramic and are coated with a thin layer of magnetic material.

They are stiff and inflexible. Because these platters spin at incredibly high speeds, any flexibility would result in catastrophic failure.

Consequently, they are sealed inside a heavy, vacuum-tight metal enclosure to prevent even microscopic dust particles from entering the system, a stark difference from the relatively open casing of a floppy.

Read and Write Mechanisms

The method used to retrieve data from these surfaces represents a major divergence in engineering philosophy. Floppy drives operate on a contact-based system.

When a user inserts a disk, the metal shutter slides open, and the read/write heads clamp down directly onto the spinning magnetic surface. It functions somewhat like a record player needle, but with magnetic pulses instead of physical grooves.

This direct physical contact creates friction, which inevitably wears down both the magnetic coating on the disk and the drive heads themselves over time.

Hard drives utilize a non-contact method to avoid this wear. The read/write heads on an HDD never actually touch the platters while they are spinning.

Instead, they ride on a microscopic cushion of air generated by the rapid rotation of the disk. The gap between the head and the platter is smaller than a human hair or a fingerprint smudge.

This “flying” mechanism allows the drive to operate at much higher speeds without damaging the delicate magnetic surface, provided the drive is not jostled or dropped while active.

Form Factor and Design

Portability defined the design of the floppy disk. The 3.5-inch and the older 5.25-inch disks were created to be handled, swapped, and carried in a shirt pocket.

The magnetic media was protected by a spring-loaded shutter and a hard plastic shell, but the system was inherently exposed. Users constantly inserted and ejected disks, which meant the drive mechanism was frequently exposed to dust and debris from the outside environment.

The entire design centered on the ability to physically transport data between machines effortlessly.

Hard drives were generally designed to remain stationary. While external hard drives eventually became common, the standard HDD form factor is a rectangular metal brick meant to be mounted permanently inside a computer case.

They connect directly to the motherboard and draw power from the system's internal supply. This fixed nature allows them to be larger, heavier, and more power-hungry than their portable counterparts.

The design prioritizes stability and protection of the internal vacuum over the convenience of being able to toss the drive into a backpack.

The Capacity and Speed Gap

While physical construction sets the baseline, the true divergence between floppy disks and hard drives becomes apparent when looking at raw performance numbers. The evolution of magnetic storage was not a linear progression but an exponential explosion in capability.

Comparing the specifications of a standard floppy disk to a modern hard drive illustrates how computing needs shifted from simple text processing to handling complex multimedia environments.

Storage Wars

The standard high-density 3.5-inch floppy disk held exactly 1.44 megabytes of data. In the context of modern computing, that number is almost difficult to visualize because it is so small.

A single high-resolution photograph taken on a smartphone today would require three or four floppy disks just to store the file. Hard drives, on the other hand, measure their capacity in terabytes. A basic 1 terabyte hard drive holds roughly the equivalent of 700,000 floppy disks.

To put this scale into perspective, filling a floppy disk is like placing a single paperback book on a desk. Filling a modern hard drive is comparable to building a massive public library, stocking every shelf with books, filling the basement with film reels, and still having room left over for a music archive.

The floppy disk forced users to be ruthless about what they saved, often deleting one file to make room for another. Hard drives effectively removed that anxiety, allowing users to hoard data without a second thought.

Performance Metrics

Capacity is only half the equation; the speed at which data moves determines the responsiveness of the entire system. Floppy disks were notoriously slow.

They typically spun at roughly 300 to 360 revolutions per minute (RPM). When a user requested a file, the drive had to spin up, and the head had to physically slide into position.

This resulted in seek times measured in tens or hundreds of milliseconds. It was a mechanical process the user could hear and feel, often accompanied by a distinctive grinding or clicking sound.

Hard drives operate in a completely different speed class. Standard desktop drives spin at 7,200 RPM, while enterprise drives can reach 15,000 RPM.

Because the platters are already spinning at high velocity and the heads float on air, the time it takes to locate data is measured in microseconds. The practical impact on the user is profound.

Copying a modest 1-megabyte file to a floppy disk was often a “coffee break” event, requiring the user to sit and wait while the progress bar crawled across the screen. On a modern hard drive, transferring that same amount of data happens so instantly that the operating system often finishes the task before it can even display a progress window.

Durability, Reliability, and Lifespan

Storage media serves a dual purpose; it must not only hold information but also preserve it against the ravages of time and the environment. While both floppy disks and hard drives use magnetic fields to secure data, their ability to protect that data varies significantly.

The design choices that made floppies portable also made them fragile, whereas the stationary nature of hard drives allowed for a level of protection that ensures data remains readable years after it was written.

Vulnerability Factors

The physical construction of a floppy disk left it exposed to a wide array of environmental threats. Because the magnetic film was only protected by a thin plastic shutter, dust and liquid could easily penetrate the casing.

A single grain of sand caught between the read head and the disk surface could scour the magnetic coating, permanently destroying data. Furthermore, the magnetic signal on a floppy was relatively weak.

Placing a disk near a strong magnet, such as a stereo speaker or even a CRT monitor, often scrambled the information. Heat was another enemy; leaving a disk on a car dashboard on a sunny day could warp the plastic casing enough to make it unreadable.

Hard drives trade these environmental weaknesses for a specific physical vulnerability. The hermetically sealed casing effectively immunizes the platters against dust, moisture, and magnetic interference from typical household objects.

However, the floating head mechanism introduces a significant risk regarding physical shock. If a hard drive is dropped or subjected to sudden impact while running, the read/write head can crash into the spinning platter.

This “head crash” physically gouges the magnetic surface, resulting in catastrophic data loss that is often unrecoverable.

Data Integrity and Preservation

Even if a floppy disk is stored perfectly, the data inside is not safe forever. Old floppies are infamous for suffering from “bit rot” or magnetic decay.

Over time, the magnetic orientation of the particles on the film loses its strength and randomness creeps in, turning valid files into corrupted gibberish. Additionally, the binder material that holds the magnetic particles to the plastic base can degrade, causing the coating to flake off.

This creates a situation where a user might store a file successfully, only to find the disk unreadable five years later despite no physical damage occurring.

Hard drives incorporate sophisticated technology to combat this inevitable decay. They utilize advanced error-correction code (ECC) algorithms that verify data integrity every time a file is read or written.

If the drive detects a minor error or a weak magnetic sector, it can often reconstruct the missing data mathematically and move it to a healthy section of the platter. While hard drives will eventually fail, their ability to maintain the coherence of the magnetic signal over a decade or more far surpasses the unreliable retention of the floppy format.

Usability and Write Cycles

The mechanism of how data is written dictates the lifespan of the device itself. Because floppy disk heads make physical contact with the recording surface, every operation involves friction.

This mechanical abrasion limits the number of times a specific sector can be written to before it fails. Heavy users of floppy disks frequently encountered “bad sectors,” which were essentially spots on the disk worn smooth by repeated use.

It was a storage medium designed for temporary transport rather than active, high-intensity workflow.

Hard drives are engineered for endurance. Since the heads hover above the platters, there is zero friction during the read/write process.

A specific sector on a hard drive platter can be overwritten millions of times without showing signs of degradation. This durability allows hard drives to serve as the active workspace for operating systems, which constantly write temporary logs and cache files in the background.

Such a workload would destroy a floppy disk in a matter of days.

The Shift in Usage

As computing hardware grew more powerful, the way we interacted with storage fundamentally changed. The relationship between the user and their data shifted from a model of constant physical interaction to one of reliability and permanence.

This transition was not just about getting more space; it was about redefining the workflow of personal computing.

The Role of the Floppy Disk

For a long time, the floppy disk was the lifeblood of the computer industry. Before the internet was ubiquitous, software came in boxes filled with physical disks.

Installing a new program often meant feeding the computer a stack of ten or twenty disks in sequence. Beyond installation, the floppy was the primary tool for troubleshooting.

If a computer failed to start, a “boot disk” was the only way to bypass the internal drive and access diagnostic tools.

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the floppy was the concept of the “Sneakernet.” In offices and schools, sharing a file didn't mean sending an email attachment.

It meant saving the document to a disk, ejecting it, walking across the room, and handing it to a colleague. This physical transfer of data was the standard for collaboration.

The floppy disk was less of a storage vault and more of a digital briefcase, essential for moving work between home and the office.

The Role of the Hard Disk

While the floppy disk handled transit, the hard drive quietly became the foundation of the entire computing experience. Early computers ran entirely from floppy disks, but as operating systems like Windows and macOS grew in complexity, they required a permanent home.

The hard drive allowed the operating system to live inside the machine, ready to launch the moment the power button was pressed.

This shift allowed for the installation of massive applications that could never fit on a portable disk. Video editing software, 3D gaming, and complex databases relied on the hard drive's ability to access thousands of files instantly.

The hard drive transformed the computer from a temporary workspace into a media center. Users began ripping their CD collections to MP3s and downloading video files, requiring a storage solution that could hold libraries of content rather than just a few text documents.

The hard drive became the digital filing cabinet that never needed to be emptied.

The Obsolescence Factor

The death of the floppy disk was inevitable, driven by the exploding size of digital files. As images became sharper and audio became clearer, the 1.44 MB limit turned from a constraint into a blockade.

A single high-quality MP3 song could not fit on a standard floppy disk. The introduction of the CD-ROM offered hundreds of megabytes of space for software distribution, eliminating the need for stacks of floppies.

Simultaneously, the USB flash drive arrived to kill the Sneakernet. These small, durable sticks offered vastly more storage without the slow speeds or mechanical fragility of magnetic disks.

High-speed internet drove the final nail in the coffin. With the ability to email large files or download software directly from a server, the need for a physical bridge between computers vanished.

The floppy disk did not disappear because it stopped working; it disappeared because the world grew too large to fit inside it.

Conclusion

The history of magnetic storage is essentially a story of compromise between mobility and capability. The floppy disk championed the idea that data should be portable.

It was the pocket-sized solution that allowed information to travel from person to person, yet it was constantly held back by its fragile nature and severe capacity limits. It sacrificed performance for the sake of being easily carried.

On the other side stood the hard drive. It was a heavy, stationary component that demanded to be anchored inside a chassis, but in exchange, it offered a vast digital warehouse and the speed necessary to run complex operating systems.

One format offered freedom of movement with strict boundaries, while the other offered immense power but required a permanent home.

Today, these two technologies have met very different fates. The floppy disk has achieved a strange sort of immortality.

It is technically obsolete, a relic found only in museums or dusty attics, yet it survives as the universal symbol for “saving” on nearly every computer screen. It persists as a cultural icon long after its magnetic film has decayed.

The hard drive, conversely, has largely disappeared from our sleek modern laptops in favor of faster Solid State Drives, but it has not vanished. Instead, it has migrated to the massive server farms that power the internet.

When we save a file to the cloud today, we are often still spinning up a magnetic platter in a distant data center. The floppy disk became a symbol, but the hard drive remains the invisible infrastructure of the digital age.