How Does Fiber Optic Internet Work? The Physics of Light

Most internet connections still rely on aging copper wiring that was originally built for analog telephone calls. Fiber optic technology abandons this outdated method completely.

Instead of pushing electrical current through resistant metal, this system shoots rapid pulses of laser light through flexible strands of pure glass. By utilizing the physics of light, these cables transmit information at velocities traditional infrastructure simply cannot touch.

The result is a connection that handles massive bandwidth without breaking a sweat.

The Physics of Transmission

Fiber optics rely on a distinct physical process to move information from one point to another. Unlike copper cables that carry electrons, these lines transmit data using photons.

This shift from electricity to light allows for greater bandwidth and distance capabilities. The process involves translating computer code into optical signals and managing how those signals travel through a glass medium.

Converting Binary to Light

All digital files, from emails to streaming movies, exist as binary code. This code is a long sequence of ones and zeros.

In a fiber optic system, a transmitter converts this electronic information into optical signals. The transmitter uses a laser or an LED to flash light rapidly into the cable.

A pulse of light represents a “one” and the absence of light represents a “zero.” These flashes occur billions of times per second.

This rapid-fire blinking creates a stream of data that travels down the line.

Total Internal Reflection

Light naturally travels in a straight line, but fiber cables must bend around corners and run underground. To keep the signal from escaping the glass strand, the technology uses a principle known as total internal reflection.

The light hits the inner walls of the cable at a shallow angle. Instead of passing through the glass and out the side, the light bounces back into the center.

This allows the signal to zigzag down the length of the cable over vast distances without losing its intensity.

The Speed of Travel

Light in a vacuum travels at approximately 186,000 miles per second. When light travels through glass, it moves somewhat slower due to the density of the material.

Fiber optic signals typically travel at about 70% of the speed of light in a vacuum. Despite this reduction, the velocity remains significantly higher than the effective throughput speeds of electrical signals in copper wire.

This allows for near-instantaneous data transfer with minimal latency.

Anatomy of a Fiber Optic Cable

A fiber optic cable is a precision-engineered component designed to protect and guide light. While it may look like a standard plastic wire from the outside, the internal structure is quite different.

Each layer serves a specific function to ensure the glass remains intact and the signal stays contained.

The Core

The innermost element is the core. This is an ultra-thin strand of extremely pure glass that serves as the pathway for the light.

In many cables, this strand is thinner than a human hair. The purity of the glass is vital because any impurities would scatter the light and degrade the signal.

The core carries the actual data stream from the source to the destination.

The Cladding

Surrounding the core is a secondary layer of glass called the cladding. While also made of glass, the cladding has a lower refractive index than the core.

This difference in density creates the mirror effect necessary for total internal reflection. Without the cladding, light would escape the core and the signal would fade after a short distance.

The cladding acts as a barrier that keeps the light focused continuously down the center of the strand.

The Buffer and Jacket

Glass is fragile, so the outer layers provide necessary protection. A plastic coating known as the buffer surrounds the cladding to absorb shock and prevent physical damage.

On top of the buffer, the cable features a tough outer jacket. This final layer protects the internal components from moisture, temperature changes, and the physical stress of installation.

Single-Mode Versus Multi-Mode

Cables fall into two primary categories based on how they carry light. Single-mode fiber has a very small core that forces light to travel in a single, direct path.

This design maintains signal integrity over long distances. Multi-mode fiber features a wider core that allows multiple light paths to travel simultaneously.

This type is generally used for shorter distances, such as connecting servers within a single data center, as the signals can disperse over long runs.

The Network Connection: From ISP to Device

Delivering internet service to a home or business requires a complete circuit. The signal must originate at the provider, travel through the infrastructure, and eventually convert into a format that consumer electronics can utilize.

This process involves specialized equipment at both ends of the connection.

The Optical Transmitter

The process begins at the Internet Service Provider (ISP) hub. Here, an optical transmitter generates the signal.

This device takes electrical data from the provider's main network and converts it into light pulses using lasers or LEDs. These transmitters are powerful enough to push the signal miles down the line towards the neighborhood or residence.

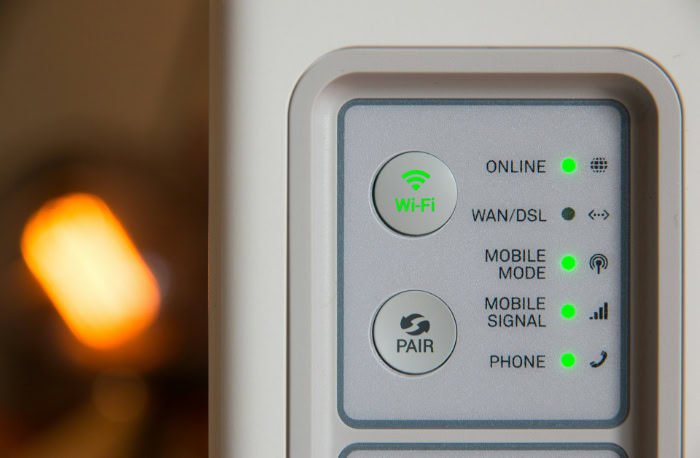

The Optical Network Terminal

At the subscriber's location, the fiber line connects to a device called an Optical Network Terminal, or ONT. This unit serves the same function as a modem in a cable setup.

The ONT is the termination point for the fiber line. It is usually installed on the side of the house or inside a utility closet where the optical cable enters the premises.

Signal Conversion

The final step is translating the language of light back into electricity. The ONT captures the incoming light pulses and instantly converts them back into electrical Ethernet signals.

Once this translation occurs, the ONT sends the data via a standard copper Ethernet cable to the user's router. The router then broadcasts the internet signal via WiFi or distributes it to wired devices, completing the connection.

The Last Mile: Connection Types

The term “fiber internet” is often used broadly, but not all fiber connections are identical. The physical configuration of the network determines the actual speed and reliability a user receives.

This variance usually occurs in the final stretch of the cabling process known as the “last mile.” This is the leg of the network that physically connects the main infrastructure to a specific residence or building.

Fiber to the Home (FTTH/FTTP)

Fiber to the Home, also called Fiber to the Premises (FTTP), represents the most direct connection available. In this setup, the fiber optic line runs all the way from the provider's central network directly into the user's living space.

There are no copper cables involved at any stage of the transmission. Because the light signal travels uninterrupted to the router, this configuration offers the maximum possible speeds and represents the purest form of fiber internet.

Fiber to the Curb (FTTC)

In a Fiber to the Curb arrangement, the optical cables run to a utility pole or a communications box located on the street near the user's property. The fiber connection terminates at this point.

To bridge the short gap between the curb and the house, the provider uses existing copper coaxial cables or telephone wires. While still faster than standard DSL, the introduction of copper for the final stretch limits the bandwidth potential compared to a direct fiber line.

Fiber to the Node (FTTN)

Fiber to the Node creates a hybrid system where the fiber optic cable ends at a centralized neighborhood box, which may be situated several streets away from the customer. From this node, the signal travels a significant distance over older copper wiring to reach the destination.

This creates a bottleneck effect. Since data moves much slower over copper than glass, the extended length of the metal wire significantly reduces the overall speed.

The further a house is from the node, the slower the connection will be.

Performance Implications: Fiber Versus Copper

The structural differences between glass and copper create distinct performance outcomes. While traditional cable internet runs on electrical signals over metal, fiber optics utilize light.

This fundamental shift in physics results in tangible improvements in how users experience the web, particularly regarding speed, reliability, and data volume.

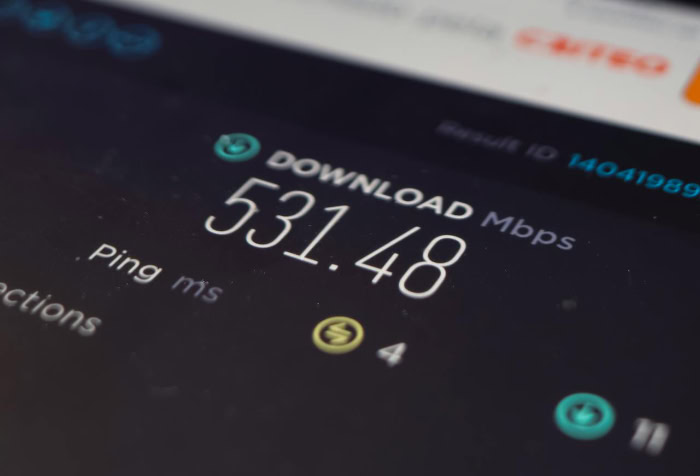

Bandwidth Capacity

Fiber optic cables possess a much larger capacity for carrying information than copper wires. A single strand of glass can transmit significantly more data at once compared to a metal cable of similar thickness.

This high bandwidth allows households to run multiple high-demand applications simultaneously without seeing a drop in performance. Users can stream 4K video, download large files, and browse the web on several devices at the same time without the network congestion common with cable internet.

Symmetrical Speeds

A major advantage of fiber is the ability to provide symmetrical speeds. Most cable connections offer fast download speeds but much slower upload speeds.

Fiber providers typically configure their networks so that the upload rate matches the download rate. This balance is essential for modern activities such as high-definition video conferencing, live streaming, and backing up large hard drives to cloud storage servers.

Latency and Signal Loss

Latency, often referred to as “ping,” is the time it takes for a signal to travel from a device to a server and back. Fiber optics offer superior latency because light signals encounter less resistance than electrical signals.

Additionally, data traveling over copper suffers from significant signal degradation, or attenuation, over long distances. Fiber optic signals can travel many miles without losing strength, ensuring that the connection remains fast and responsive regardless of how far the user is from the ISP's main hub.

Immunity to Interference

Copper wires act like antennas and can pick up electromagnetic interference from nearby power lines, heavy machinery, or even lightning storms. This interference introduces noise into the line which causes errors and slows down the connection.

Glass is a dielectric material, meaning it does not conduct electricity. Consequently, fiber optic cables are completely immune to electromagnetic interference.

This physical property ensures the connection remains stable and consistent even during harsh weather or in areas with high electrical activity.

Conclusion

Fiber optics fundamentally change the way we connect to the internet by replacing electrical impulses with pulses of light. By trapping these signals inside hair-thin strands of glass, the technology allows data to travel at velocities that traditional copper wiring simply cannot match.

Building this network requires significant effort and investment, as it often involves laying entirely new physical lines rather than utilizing existing telephone infrastructure. Despite the complexity of installation, fiber has established itself as the modern benchmark for high-speed connectivity.

As the demand for bandwidth grows, the distinction between a direct fiber connection and a hybrid setup becomes critical. Recognizing these differences allows consumers to look past marketing terms and select the internet service that truly meets their performance needs.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is fiber optic internet faster than cable?

Fiber is generally much faster because it uses light signals instead of electricity. This allows data to travel over longer distances without slowing down or degrading. While cable internet can offer high download speeds, fiber provides symmetrical speeds, meaning uploads are just as fast as downloads.

Do I need a new modem for fiber internet?

You cannot use a traditional cable modem with a fiber connection. Fiber networks require an Optical Network Terminal (ONT) to convert light pulses into electrical signals. Your provider will typically install this device inside your home or on an outside wall to connect with your router.

Does bad weather affect fiber internet?

Fiber optic cables are made of glass and do not conduct electricity, so they are immune to interference from lightning or electrical storms. While severe physical damage to the lines can cause outages, the signal itself does not degrade due to rain, moisture, or extreme heat like copper wires often do.

What is the difference between FTTH and FTTN?

Fiber to the Home (FTTH) runs a pure fiber line directly into your residence for maximum speed. Fiber to the Node (FTTN) runs fiber to a neighborhood box and uses old copper wiring for the rest of the distance. This copper segment often creates a bottleneck that slows down the connection.

Why does fiber offer symmetrical speeds?

Traditional copper networks dedicate most of their bandwidth to downloads because users historically consumed more content than they created. Fiber optics have a much higher total capacity, which allows providers to offer equal lanes for traffic. This means you can upload large files or stream video just as fast as you download data.