How Does The Internet Work? Your Connection Explained

We often discuss “the cloud” as if our data drifts through the ether, untethered and invisible. The reality is far more grounded.

The internet is a tangible colossus built from thousands of miles of glass fibers stretched across the ocean floor and massive computers humming in windowless rooms. It is not a singular machine but a network of networks that links billions of devices together.

Seeing past the screen reveals a complex system of logical rules and heavy hardware.

The Physical Infrastructure: Hardware and Connections

The internet often feels weightless and abstract, but it relies on a massive grid of physical objects stretching across the globe. This system requires hard lines to transmit signals, vast warehouses to store information, and specific equipment to deliver data into a home or office.

It is a tangible machine that spans the planet, comprised of heavy machinery and delicate glass fibers.

The Backbone

While satellites play a role in communication, the heavy lifting of the global internet happens underwater. Approximately 99% of international data traffic travels through submarine fiber-optic cables.

These cables are about the size of a garden hose and contain hair-thin strands of glass capable of transmitting data as pulses of light. They run across the ocean floor to connect continents, linking New York to London or Tokyo to Los Angeles.

Laying these cables is an expensive and arduous process that involves specialized ships slowly unraveling thousands of miles of line. They are engineered to withstand high pressure and harsh conditions, yet they remain vulnerable to anchors, trawling nets, and natural disasters.

When a cable is severed, internet traffic must be rerouted instantly to other lines to prevent a blackout, demonstrating the redundancy built into this global grid.

The Servers

The “places” you visit online, such as websites or streaming services, live on specialized computers known as servers. These machines do not have screens or keyboards; they are powerful hard drives and processors stacked in racks within massive facilities called data centers.

A data center acts as the physical library of the internet.

These facilities consume enormous amounts of electricity to power the machines and the industrial cooling systems required to keep them from overheating. Companies operate these centers in strategic locations worldwide to ensure that data is stored close to users, reducing the time it takes for a web page to load.

When you access a file, you are essentially remotely controlling one of these servers to copy data and send it to you.

The Last Mile

Data travels from data centers across the backbone until it reaches a local network, usually managed by an Internet Service Provider (ISP). This final leg of the connection is often called “the last mile,” even if the distance is much greater.

This is the link that connects a specific building to the broader global network.

ISPs use various technologies to bridge this gap. Older systems rely on copper telephone lines (DSL) or coaxial cables originally built for television.

Modern connections increasingly use fiber-optic lines directly to the home, offering significantly higher speeds. In rural areas where running cables is impractical, wireless towers or satellite dishes serve as the primary link to the outside world.

Home Hardware

Once the ISP brings the connection to a building, two distinct pieces of hardware manage the traffic inside. The modem serves as the translator.

It takes the raw signal coming from the wall, light from fiber, or electrical signals from copper, and converts it into digital data that computers can process. Without a modem, the signal from the street is unintelligible to your devices.

The router acts as the traffic controller. It connects to the modem and distributes the internet connection to all the devices in the house, either through Ethernet cables or Wi-Fi.

It assigns local addresses to phones, laptops, and smart TVs to ensure that when you request a website on your phone, the data doesn't appear on your television screen instead. While many modern devices combine the modem and router into a single box, their functions remain distinct.

The Addressing System: Finding Your Way

A global network connecting billions of machines would be chaotic without a precise method for locating specific devices. Just as a postal service needs a street address to deliver a package, the internet relies on a rigorous system of digital coordinates to ensure data arrives at the correct destination.

IP Addresses

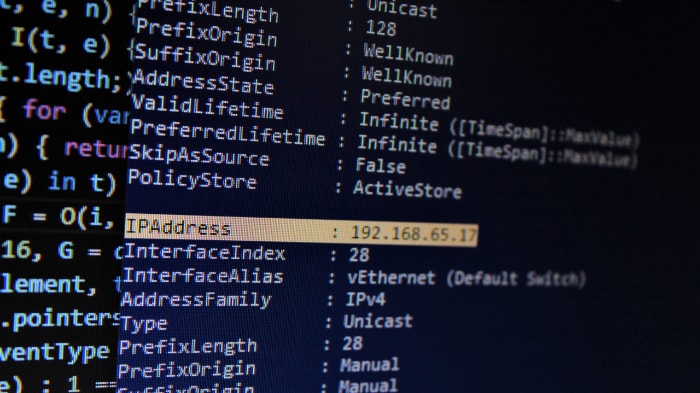

Every device connected to the internet must have a unique identifier known as an Internet Protocol (IP) address. This is a string of numbers separated by periods, such as 192.0.2.1, which acts as the device's digital location.

When a computer sends a message, it stamps the packet with its own IP address (the return address) and the destination's IP address.

There are two main versions of this system. IPv4 uses the standard format of four number blocks, but the explosion of connected devices has exhausted the available combinations.

The newer standard, IPv6, uses a much longer alphanumeric string to ensure that we never run out of addresses, accommodating everything from refrigerators to wristwatches.

Domain Names

While computers operate efficiently using long strings of numbers, humans do not. Memorizing the IP address for every favorite website would be impossible.

To solve this, the internet uses domain names, such as google.com or wikipedia.org. These names act as masks that sit on top of the numerical IP addresses. They are easy to spell, remember, and identify.

The Domain Name System (DNS)

The bridge between human-readable names and machine-readable numbers is the Domain Name System (DNS). It functions essentially as the phonebook of the internet.

When a user types a web address into a browser, the computer does not know where to go initially. It contacts a DNS server to ask for the IP address associated with that name.

This search happens in a hierarchy. If the local DNS server does not know the address, it queries “Root Servers” and “Top-Level Domain” (TLD) servers that manage endings like .com, .org, or .net.

Once the correct number is found, the DNS server returns the IP address to the user's computer, allowing the connection to proceed. This entire lookup process usually takes only a fraction of a second.

The Rules Of Communication: Protocols And Packets

Connecting hardware and assigning addresses is only half the equation. For different types of computers running different operating systems to communicate effectively, they must agree on a standard set of rules.

These rules, known as protocols, dictate how data is formatted, sent, received, and confirmed.

TCP/IP

The foundational rules of the internet are collectively known as the TCP/IP suite. This stands for Transmission Control Protocol and Internet Protocol.

These two protocols work in tandem to manage the flow of information. IP is responsible for the addressing and routing, acting like the envelope that directs the letter. TCP is responsible for the delivery and reliability, ensuring that the letter actually arrives and that the contents are intact.

This standardization allows a Windows laptop to communicate seamlessly with a Linux server or an iPhone. Without this common language, the internet would consist of isolated islands of incompatible devices unable to exchange information.

Packet Switching

When a large file, such as a high-definition video or a high-resolution image, travels across the network, it is not sent as a single continuous block. Instead, the system uses a method called packet switching.

The data is chopped into thousands of tiny, manageable chunks called packets.

Each packet carries a piece of the data along with header information indicating its order and destination. This method is highly efficient because it prevents a large file from hogging the line.

If one route is congested, individual packets from the same file can travel through different pathways across the web to reach the destination faster. They weave through the network independently, maximizing the available bandwidth.

Reassembly

Once these scattered packets arrive at the destination computer, the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) takes over to manage reassembly. Because packets may travel different routes, they often arrive out of order; packet #5 might arrive before packet #2.

The receiving computer reads the header information on each packet and arranges them back into the correct sequence. If a packet is missing or arrives corrupted, the TCP layer detects the gap and sends a request back to the sender to re-transmit that specific piece.

Only when all packets are accounted for and perfectly aligned does the computer present the complete file, image, or email to the user. This verification ensures that the internet remains reliable even when connections are unstable.

The Transaction: The Client-Server Model

Most interactions on the internet follow a specific pattern of demand and supply. This relationship is not a broadcast where information is simply pushed out to everyone at once.

Instead, it is a precise conversation between two distinct entities. This structure ensures that users receive exactly what they ask for, whether it is a specific video, a banking portal, or a news article.

The Request

In this relationship, the device you are holding is known as the “client.” Whether it is a smartphone, a laptop, or a smart thermostat, the client's primary role is to initiate contact.

The process begins when a user takes an action, such as clicking a link or hitting “Enter” after typing a search query.

This action triggers the client to construct a formal request. This request is a digital message sent out across the network, asking a specific computer elsewhere to provide data.

The client remains passive until the user interacts with it, but once triggered, it aggressively seeks out the information required to fulfill the user's command.

The Response

On the other end of the line sits the server. As the name implies, its job is to serve the client.

These powerful computers operate in a perpetual state of readiness, waiting for incoming requests. When a server receives a demand from a client, it interprets the request and searches its internal storage for the relevant resources.

These resources might include image files, text documents, or lines of code. Once the server locates the necessary components, it bundles them into a package and transmits them back to the specific IP address of the client.

If the server cannot find what was asked for, it sends back an error code, such as the famous “404 Not Found,” indicating that the request reached the machine but the content was missing.

The Handshake

Before any actual content is exchanged, the client and server must agree to communicate. This initial step is often called the “handshake.”

It is a rapid exchange of preliminary signals where the two machines acknowledge one another and synchronize their internal clocks to ensure smooth data transmission.

In modern browsing, this step also involves strict security measures. If a website uses HTTPS, the handshake includes an exchange of security certificates.

This process, often powered by SSL (Secure Sockets Layer), creates an encrypted tunnel between the two machines. It ensures that even if someone intercepts the data while it travels through the cables, they cannot read it.

This is visually represented by the padlock icon often seen in browser address bars.

The Application Layer: The Web vs. The Internet

It is common to use the terms “Internet” and “World Wide Web” interchangeably, but they refer to two distinctly different concepts. Conflating them is like confusing the railroad tracks with the trains that run on them.

To grasp how the digital experience comes together, one must distinguish the physical infrastructure from the services that utilize it.

Infrastructure vs. Service

The Internet is the massive network of hardware and connections. It includes the copper wires, fiber-optic cables, routers, and the IP addressing system.

It is the foundation that allows computers to connect.

The World Wide Web, conversely, is merely one of the many services that run on top of that infrastructure. It is a collection of documents and applications linked together.

While the internet also carries emails, file transfers, and app data, the Web specifically refers to the pages and sites navigated via hyperlinks. The Internet provides the road; the Web is the traffic moving along it.

Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP)

The Web relies on a specific protocol to function, known as HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol). This is the set of rules that governs how web pages are formatted and transmitted.

When you see “http” or “https” at the start of a URL, it tells the browser to use this specific language to communicate with the server.

This protocol defines how messages are formatted and how the server and client should respond to various commands. It allows for the retrieval of interlinked text documents (hypertext) which creates the “web” of connections that users navigate daily.

Without this standardized protocol, the chaotic mix of text and media on the web would be impossible to organize or view consistently.

Browsers As Translators

The final piece of the puzzle is the web browser. Applications like Chrome, Safari, or Firefox act as translators for the user.

When a server sends a response, it does not send a screenshot of the website. It sends raw code, primarily HTML (structure), CSS (style), and JavaScript (functionality).

To the average human, this code is an unreadable wall of text and symbols. The browser's job is to take these instructions and “render” them into a visual interface.

It reads the HTML to know where the text goes, applies the CSS to determine the colors and fonts, and runs the JavaScript to make buttons interactive. This rendering happens in milliseconds, creating the illusion that the website arrives fully formed on the screen.

Conclusion

The seemingly instant appearance of a web page belies the immense physical distance the data travels. A simple click initiates a signal that moves from a home router to a local provider before entering the vast fiber-optic backbone.

This pulse of light often traverses the ocean floor to reach a data center on another continent. There, a server locates the requested files, breaks them into thousands of packets, and sends them hurling back through the network.

Your device catches these fragments, reassembles them, and translates the code into a visible interface, all within the span of a heartbeat.

This global system is a feat of engineering that balances heavy infrastructure with precise logic. It relies on glass strands, copper wires, and strict protocols to function correctly.

While it often feels invisible and automatic, the internet is a constructed reality that requires constant maintenance and energy. It binds the modern world together not through magic, but through a relentless cycle of request and response that happens billions of times every day.