How to Browse the Web Anonymously: Stop Being Tracked

Browsing the web anonymously is less about achieving perfect invisibility and more about actively managing what you reveal to the world. In practice, true anonymity means obscuring your identity, masking your physical location, and preventing your online activity from being easily linked back to you.

While no single tool guarantees complete secrecy, reducing your digital footprint makes it significantly harder for outside observers to track your movements.

What Online Anonymity Really Means

Many internet users confuse the feeling of being invisible with actually being invisible. True online anonymity is a specific state where your actions cannot be connected to your real-world identity.

It is distinct from simply keeping secrets or cleaning up a browser history.

Anonymity vs. Privacy vs. Incognito Mode

These terms are often used interchangeably, but they represent distinct concepts with different goals. Privacy refers to the ability to control who sees your data and what they do with it.

You can have privacy without anonymity. For example, when you post on a locked social media profile, your friends know exactly who you are, but the public cannot see your content.

You are identified, but your data is private. Anonymity is stricter. It ensures that your actions cannot be tied back to you at all.

“Incognito” or “Private Browsing” modes often cause the most confusion. These features prevent your computer from saving your history, cookies, and form data locally.

If someone opens your laptop after you finish a session, they will not see where you went. However, the websites you visited, your internet service provider, and the network administrator can still see everything you did. Incognito only protects you from people in your physical space, not from the internet itself.

Who Can See Your Traffic?

When you connect to a website, your data passes through several hands before reaching its destination. The first observer is usually your Internet Service Provider (ISP).

Because they provide the connection to your home or mobile device, they can see every domain you visit. In many regions, they are legally permitted to log this activity and sell the data to marketing firms.

If you browse at work, school, or on a public Wi-Fi network, the network owner acts as another layer of surveillance. They have full visibility over the traffic moving through their router.

Employers often use this to monitor productivity, while campus administrators may use it to enforce usage policies.

On the other end of the connection, websites and advertisers are waiting. They use trackers, cookies, and invisible pixels to build a profile of your interests.

Data brokers then aggregate this information, often combining your online habits with offline records like voter registration or credit card purchases to create a comprehensive dossier that links your browsing habits directly to your name and address.

Common Myths and Limits

A dangerous assumption is that a single tool can provide a magical shield against all surveillance. Installing a VPN or using the Tor browser significantly improves your security posture, but neither makes you a ghost.

If you use Tor but log into your personal email account, you have immediately broken your anonymity because the site now knows exactly who is accessing it.

Another pervasive myth is that anonymity must be absolute to be useful. In reality, the goal is risk reduction.

You are trying to remove enough linking data to make tracking you difficult, expensive, and time-consuming. No system is perfect.

Sophisticated adversaries with enough resources can often find ways to de-anonymize users through complex traffic analysis. Success comes from layering defenses rather than relying on one specific software solution to do all the work.

Understanding Your Exposure and Risk Level

Achieving anonymity requires a clear assessment of how you are currently being tracked and whom you are trying to evade. Every time you connect to the internet, you leave behind a trail of data points that can be assembled to identify you.

Your Digital Identifiers

Websites and networks use several mechanisms to recognize users. The most basic is the IP address, a numerical label assigned to your device by your internet service provider.

It functions like a digital return address, revealing your general geographic location and the specific network you are using. While an IP address does not always contain your name, it connects your activity to a billing account held by your ISP.

Cookies serve as another primary tracking method. These small text files are saved to your device by websites to remember your preferences or login status.

However, third-party tracking cookies allow advertisers to follow you across different sites, building a history of where you have been. Even if you clear your cookies, you may still be tracked through browser fingerprinting.

This technique collects details about your device configuration, such as screen resolution, installed fonts, operating system version, and battery level. When combined, these data points create a unique profile that can identify your device among millions of others without ever placing a file on your hard drive.

The most obvious but often overlooked identifier is a user account. Logging into a platform like Google, Facebook, or Amazon instantly links all current browsing activity to your verified identity.

No amount of encryption or IP masking can protect your anonymity if you voluntarily authenticate yourself with a service that knows who you are.

Defining Your Threat Model

Security professionals use the term “threat model” to describe the process of identifying who wants your data and how much effort they will expend to get it. A casual user who simply wants to avoid targeted advertising has a low-risk threat model.

They might only need a privacy-focused browser and an ad blocker. The adversary here is a marketing algorithm, not a human investigator.

If your goal is to hide your activity from an employer or a strictly monitored campus network, the risk level increases. In this scenario, the network administrator has direct access to your traffic logs.

You need tools that encrypt your connection, such as a VPN, to prevent local snooping. The stakes are higher here, involving potential job loss or academic suspension.

The highest risk level involves protecting against state-level surveillance or persistent cyberstalking. Activists, journalists, and whistleblowers often face adversaries with significant resources and legal authority to demand data from ISPs.

For these users, a simple VPN is insufficient. They require the robust, multi-layered protection of the Tor network and rigorous operational security to ensure no single mistake reveals their location.

Legal, Policy, and Ethical Boundaries

Using privacy tools is generally legal in most jurisdictions, but the context matters. In many Western countries, using Tor or a VPN is a standard practice for security professionals and privacy advocates.

However, in nations with strict internet censorship, the act of using these tools can itself be a crime or a flag for further investigation. Users must be aware of the laws governing encryption and anonymity software in their specific physical location.

Beyond the law, you must consider the policies of the networks and services you use. Bypassing a school firewall or violating a website’s terms of service can result in bans or legal action, even if the underlying technology is legal.

Anonymity grants power, but it does not grant immunity from consequences if your identity is eventually discovered. It is vital to operate within the boundaries of your own risk tolerance and ethical standards.

Core Tools for Anonymous Browsing

Once you have identified your threat model, the next step involves selecting the right infrastructure to obscure your digital footprint. Browser settings alone cannot hide your location or encrypt your traffic from outside observers.

To achieve genuine anonymity, you must alter the path your data travels through the internet.

VPNs and Encrypted Connections

A Virtual Private Network (VPN) is the most common tool for masking an IP address. When you activate a VPN, it creates an encrypted tunnel between your device and a remote server operated by the VPN provider.

Your internet service provider can see that you are sending data, but they cannot read the contents of that data or see which websites you are visiting. The website on the other end sees the IP address of the VPN server rather than your home or mobile IP, effectively masking your physical location.

Trust is the most critical variable when using a VPN. By using one, you are essentially shifting your trust from your ISP to the VPN company.

While your ISP can no longer log your browsing history, the VPN provider technically has the ability to do so. It is vital to select a reputable provider, such as NordVPN, with a proven “no-logs” policy that has been audited by third-party security firms.

Furthermore, users should configure strong settings, such as a “kill switch,” which automatically cuts your internet connection if the VPN drops, ensuring that no traffic accidentally leaks out over an unencrypted line.

Tor and Onion Routing

For users requiring a higher level of anonymity than a commercial VPN can provide, the Tor network is the gold standard. Tor, short for “The Onion Router,” directs internet traffic through a free, worldwide, volunteer overlay network consisting of more than seven thousand relays.

The name comes from the way it handles encryption in layers, much like an onion. Your data is encrypted multiple times and sent through a random sequence of nodes.

The entry node knows who you are but not what you are doing. The middle node knows nothing about the origin or the destination. The exit node knows which site you are visiting but not who you are.

This decentralized structure makes it incredibly difficult for anyone to trace a connection back to the user. However, this protection comes with significant trade-offs.

Because your data must hop through multiple servers around the world, browsing speeds are often noticeably slower than a standard connection. Additionally, many websites automatically block traffic from known Tor exit nodes or present frequent CAPTCHA challenges, making the browsing experience frustrating for daily tasks.

Tor is best reserved for activities where anonymity is more important than speed or convenience.

Proxies and Related Network Tools

Proxies function similarly to VPNs but are generally less secure and more lightweight. A proxy server acts as a simple intermediary or gateway between you and the internet.

When you request a webpage, the request goes to the proxy, which then retrieves the page and sends it to you. This hides your IP address from the target website. However, unlike a VPN, standard proxies often do not encrypt your traffic.

This means your ISP or a hacker on a public Wi-Fi network can still see exactly what you are doing.

Proxies are typically used for bypassing basic geographic restrictions rather than for serious privacy protection. A related concept is Secure DNS (Domain Name System).

Normally, your ISP handles the “phonebook” lookup that translates a domain name like “example.com” into an IP address. By configuring your browser or router to use an encrypted DNS provider, you prevent your ISP from seeing the list of domains you are looking up.

While Secure DNS does not hide your IP address from websites, it closes a common leak that often compromises privacy even when other protections are in place.

Hardening Your Browser and Search Habits

Securing your internet connection is only half the battle. If your network traffic is encrypted but your browser is leaking data, advertisers and trackers can still identify you with ease.

The software you use to access the web acts as your window to the world, but it also functions as a primary data collector for technology companies.

Private and Privacy-Focused Browsers

Most popular web browsers are built by advertising companies that profit from user data. Using them often means fighting against the software's default behavior to maintain your privacy.

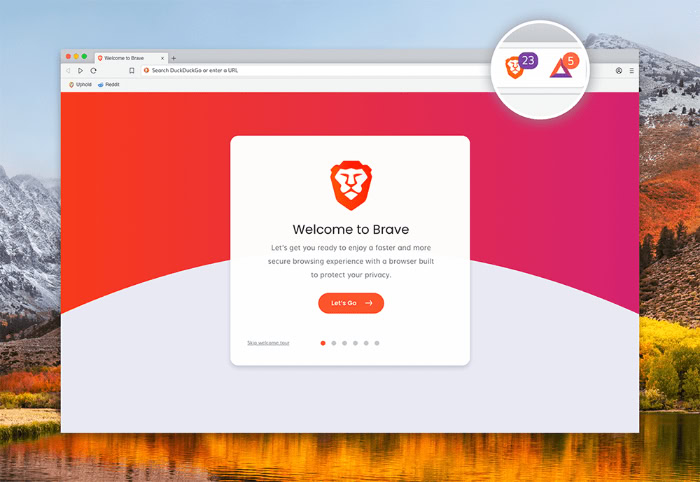

Privacy-focused alternatives like Firefox, Brave, or LibreWolf take the opposite approach. They come pre-configured to strip out telemetry and stop websites from following you.

Some are “hardened” versions of standard browsers, stripped of all code that might report back to a central server. While standard “private” or “incognito” modes are useful for local hygiene, ensuring that someone borrowing your computer cannot see your history, a dedicated privacy browser prevents the sites themselves from recognizing you.

These browsers often include features that automatically wipe your session data the moment you close the application.

Blocking Trackers and Reducing Fingerprinting

Ad blockers are often viewed as convenience tools, but they are actually security necessities. Extensions like uBlock Origin do more than just hide annoying banners.

They prevent third-party scripts from loading, effectively stopping invisible trackers from pinging marketing servers. However, blocking cookies is not enough to stop browser fingerprinting.

This sophisticated technique analyzes your screen resolution, installed fonts, graphics card drivers, and even battery status to create a unique ID. Anti-fingerprinting features, found in specialized browsers, attempt to blend your traffic in with other users by reporting generic information.

Instead of reporting your specific system details, the browser lies and reports a generic configuration, making you look identical to thousands of other users.

Search Engines and Cookie Hygiene

Your search history is a window into your thoughts, health concerns, and financial status. Mainstream search engines log every query and tie it to your profile to serve targeted ads.

Switching to a private search engine like DuckDuckGo or Startpage breaks this chain. These services fetch results without recording your IP address or saving your search terms.

Furthermore, maintaining cookie hygiene is vital. Leaving cookies on your machine for months allows data aggregators to build a long-term timeline of your life.

Configuring your browser to automatically delete all cookies and site data every time you close the window ensures that every session starts with a clean slate, preventing long-term profiling across different days and weeks.

Safe Day‑to‑Day Anonymous Browsing Practices

Technical tools can mask your connection, but they cannot fix human error. The most robust encryption in the world fails the moment you voluntarily hand over your personal details to a website.

Maintaining anonymity requires a shift in behavior. You must treat your online actions with discipline, ensuring that your real life and your anonymous activities never intersect.

Separating Identities and Sessions

One of the fastest ways to compromise yourself is through cross-contamination. This occurs when you mix your anonymous activity with your real-world identity in the same browsing session.

For instance, if you log into a personal social media account in one tab while browsing a sensitive site in another, cookies or browser fingerprinting can easily link the two activities. To prevent this, strict compartmentalization is necessary.

You should establish different “personas” for different activities. Use a standard browser like Chrome or Safari for your banking, streaming, and social media, where you are already identified.

Then, use a completely separate, hardened browser or a different profile for your anonymous searching. Never mix these environments.

If you need to check a private email while using your anonymous setup, ensure that the email account itself was created anonymously and has no ties to your phone number or real name. Treating these sessions as if they belong to two different people helps maintain the mental and technical barriers needed for protection.

Handling Logins, Payments, and Downloads

Logging into a service is the ultimate deanonymizer. As soon as you enter a username and password, you tell the server exactly who is behind the encrypted connection.

If a site requires an account, you must create one that has no link to your actual identity. This means using a dedicated email address that you do not use for anything else.

Financial transactions are equally revealing. Credit cards and bank transfers create permanent records that trace back to you.

While cryptocurrency is often cited as a solution, most public ledgers are traceable by determined analysts. Prepaid gift cards purchased with cash or privacy-centric cryptocurrencies offer better protection, though they are harder to use.

Downloading files introduces another set of risks. A PDF, image, or Word document often contains metadata, hidden information about the author, creation date, and software used.

Furthermore, opening a file can sometimes trigger it to “phone home” or connect to the internet to load a font or script. If this happens outside your VPN or Tor connection, your real IP address is exposed. It is safer to strip metadata before opening files and to view them while offline or inside a secure, isolated virtual machine.

Avoiding Common Deanonymization Mistakes

Small slips can undo months of careful operational security. A frequent error is connecting to public Wi-Fi without a VPN.

Doing so leaves your traffic wide open to anyone else on the network, including the network administrator. Another major pitfall is username reuse.

If you use the handle “SkyWalker99” on a gaming forum and then use the same name on a private message board, a simple search connects the two identities, potentially leading back to your real email or social media profiles.

Finally, users often compromise themselves by trying too hard to be secure. Over-customizing your browser with dozens of privacy extensions can actually make you easier to track.

By creating a highly unique combination of fonts, window sizes, and plugins, you make your browser fingerprint stand out from the crowd. The goal is to blend in, so keeping your software settings relatively generic often provides better cover than a highly customized setup that looks like a unique snowflake to tracking algorithms.

Conclusion

Effective anonymous browsing is not a product you buy but a process you maintain. It relies on a three-layered approach: securing your connection with network tools like VPNs or Tor, hardening your browser to block trackers and leaks, and adopting disciplined daily habits to prevent accidental exposure.

Neglecting any single layer weakens the entire system. A VPN cannot stop you from logging into a tracked account, and a secure browser cannot hide your IP address from your internet provider.

Ultimately, you must choose a level of anonymity that is practical for your life. Most users do not need the extreme operational security of a whistleblower; for many, simply blocking ads and using a private search engine is sufficient.

However, your threat model may evolve over time. Regularly reviewing your digital footprint and updating your tools ensures that your defenses remain effective against new tracking methods.

Privacy is a dynamic challenge, and staying anonymous requires staying adaptable.