Understanding GPS: The Global Positioning System

You rely on the Global Positioning System every time you order a ride or tag a location in a photo. This complex network of satellites silently orbits thousands of miles above to answer a single question: “Where am I?” While most users associate GPS strictly with driving directions, its influence extends far beyond a simple map application.

It synchronizes financial markets to the millisecond and guides emergency responders to accurate locations. Originally developed by the U.S. Department of Defense, this technology has transformed from a military asset into a global utility.

The Fundamentals: Origins and Ownership

The Global Positioning System is a sophisticated navigation tool that serves as a global utility for timing and location data. While most people interact with it through simple smartphone applications, the system represents a significant achievement in engineering and orbital mechanics.

It operates as the most widely used component of the broader Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) family, which includes other international systems like Europe’s Galileo and Russia’s GLONASS.

Deconstructing the Acronym

GPS stands for Global Positioning System. The name refers specifically to the American satellite navigation system, even though people often use the term as a generic label for any satellite-based location technology.

It provides two primary types of data: position and time. A receiver uses these variables to calculate velocity and direction.

While other nations have developed their own versions of this technology to ensure independent capabilities, the American system remains the most universally supported standard across consumer electronics and industrial equipment.

History and Ownership

The United States Department of Defense originally conceived the project in the 1970s to overcome the limitations of previous navigation systems. The military required a reliable method to track assets and coordinate troop movements globally.

The first satellite launched in 1978, but full operational capability was not reached until the mid-1990s. Today, the system is owned by the United States government and operated by the United States Space Force.

This branch of the armed services manages the constellation to ensure it remains operational for both military and civilian users.

Accessibility for Global Use

Despite its military roots and active management by the Space Force, the system is available for civilian use worldwide without direct fees. The signal broadcast by the satellites, known as the Standard Positioning Service, is available to anyone with a compatible receiver.

There are no subscription costs or usage limits for accessing the satellite signals themselves. This open-access policy has allowed industries ranging from aviation to agriculture to build their operations around this reliable data source.

The Infrastructure: The Three Segments of GPS

The system functions through the interaction of three distinct operational components. These components work in unison to maintain accuracy and ensure that users on the ground receive reliable data.

Engineers refer to these three pillars as the space segment, the control segment, and the user segment.

The Space Segment

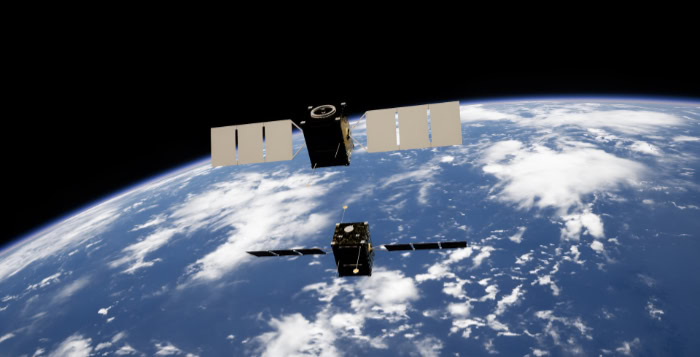

The space segment consists of a constellation of satellites orbiting approximately 12,550 miles above the Earth. The baseline design requires 24 operational satellites to ensure that at least four are visible from almost any point on the planet at any given time.

In practice, the United States typically maintains more than 30 satellites in orbit to provide redundancy and improved accuracy. These satellites circle the Earth twice a day in precise orbits.

Each satellite is equipped with solar panels for power and atomic clocks for timekeeping. Their primary job is to continuously broadcast their identity, status, and precise time to the surface below.

The Control Segment

The control segment is responsible for the health and accuracy of the satellite constellation. It consists of a global network of ground facilities, including a master control station, alternate master control stations, and various command and monitoring antennas distributed around the world.

Personnel at these facilities track the satellites as they pass overhead and monitor their transmissions. They perform crucial maintenance tasks such as correcting orbital drifts and adjusting the atomic clocks on board the satellites.

Without this constant supervision and correction from the ground, the accuracy of the system would drift significantly within days.

The User Segment

The user segment includes the millions of receivers that process the signals sent from space. This category encompasses everything from the chip inside a smartphone to complex navigation units in aircraft and shipping vessels.

A GPS receiver is a passive device; it only listens to signals and does not transmit any data back to the satellites or the control stations. The receiver captures the radio waves broadcast by the satellites and uses the embedded data to calculate its exact position on Earth.

The Mechanics: How GPS Determines Location

Determining a specific location on Earth requires complex mathematics and physics working in the background. The receiver effectively solves a geometry problem in real-time by analyzing the signals it detects from space.

This process relies on calculating the distance between the user and multiple known points in orbit.

Trilateration Explained

The core method for determining location is called trilateration. While often confused with triangulation, which measures angles, trilateration relies entirely on distance measurements.

A receiver calculates its distance from a single satellite, which places the user somewhere on the surface of a vast sphere surrounding that satellite. By measuring the distance to a second satellite, the possible location narrows to the circle where the two spheres intersect.

A third satellite narrows the position down to two specific points. Since one of those points is usually far out in space or deep within the Earth, the receiver can discard it and identify the correct location.

For a precise 3D position that includes altitude, the receiver must lock onto a fourth satellite.

The Role of Time

Precise timing is the critical variable that makes distance measurement possible. Satellites and receivers determine distance by measuring the time it takes for a radio signal to travel from space to Earth.

Because radio waves travel at the speed of light, even a microsecond of error can result in a location discrepancy of nearly 1,000 feet. To prevent this, satellites carry atomic clocks that are accurate to within billionths of a second.

The receiver compares the time the signal was transmitted with the time it was received. This difference, known as the “time of flight,” allows the device to calculate the exact distance to the satellite.

Data Independence

A common misconception is that GPS requires a cellular connection or internet access to function. This is incorrect.

The receiver in a phone or car works by listening to radio signals directly from the satellites, which works completely independently of cellular networks. Map applications often require data to download the visual map images or traffic information, but the location coordinates themselves are derived solely from the satellite link.

A user can be in a remote desert with zero cellular coverage and still see their precise latitude and longitude as long as their device has a clear view of the sky.

Beyond Maps: Critical Applications and Benefits

While the most visible function of GPS is helping drivers find their way to a new destination, the technology serves as a hidden foundation for much of modern society. The precise data provided by the satellite constellation supports industries that have little to do with travel.

From ensuring the stability of electrical grids to automating harvest machinery, the system provides a layer of certainty that businesses and governments rely on daily.

Navigation and Transportation

The most direct application remains the guidance of vehicles across land, sea, and air. Personal drivers use turn-by-turn directions to avoid traffic and find efficient routes.

In the logistics sector, trucking fleets rely on the system to track shipments in real-time, which allows companies to predict delivery times with high accuracy. Aviation has also shifted away from ground-based radar systems toward satellite-based navigation.

This transition allows pilots to fly more direct routes and land safely in difficult weather conditions. Maritime operations use similar capabilities to steer ships through narrow channels and track vessels across the open ocean.

Safety and Emergency Response

The ability to pinpoint a location instantly can be the difference between life and death during an emergency. Search and Rescue teams use GPS to locate lost hikers in remote wilderness areas where visual searches would be impossible.

In urban environments, the Enhanced 911 (E911) system uses location data from mobile phones to direct first responders to the exact site of a call. This is vital when a caller is incapacitated or does not know their specific address.

Disaster relief organizations also use the technology to map damage zones after hurricanes or earthquakes to coordinate the delivery of supplies to the areas that need them most.

Commercial and Industrial Operations

Heavy industry and agriculture have integrated satellite positioning to increase efficiency and reduce waste. In a practice known as precision agriculture, farmers use GPS-guided tractors to plant seeds and apply fertilizer with centimeter-level accuracy.

This prevents overlap, saves fuel, and maximizes crop yields. Construction crews and land surveyors use the system to map terrain and verify that structures are built exactly according to the blueprints.

The technology allows surveyors to measure vast distances and complex property lines significantly faster than traditional manual methods allowed.

Global Timing and Synchronization

One of the most critical yet least understood functions of the system is time transfer. Because each satellite carries a highly accurate atomic clock, the signal provides a universal time reference.

Financial markets use this precise timing to timestamp millions of trades per second, which prevents fraud and maintains a clear record of transactions. Cellular networks use the timing signal to synchronize their towers so calls can hand off seamlessly from one to another.

Electrical power grids also rely on this synchronization to manage the flow of current and prevent blackouts across vast distribution networks.

Accuracy, Limitations, and Challenges

Despite the sophisticated engineering behind the system, GPS is not infallible. Users often experience “drift” or errors where their reported location jumps around or appears on the wrong side of the street.

These inaccuracies usually stem from environmental factors or hardware limitations rather than a failure of the satellites themselves. The signal traveling from space is weak by the time it reaches Earth, which makes it susceptible to interference and blockage.

Signal Obstructions and Environment

The most common cause of inaccuracy is a lack of a clear line of sight to the sky. In city centers, tall skyscrapers can block signals entirely or bounce them off glass and steel surfaces before they reach the receiver.

This phenomenon is known as “multipath error.” When the signal bounces, it travels a longer path than a direct line, which confuses the receiver into calculating a position that is further away than reality.

This is why a location dot on a map often jumps erratically when a user walks among tall buildings. Similar issues occur in nature, where dense tree canopies, deep canyons, or tunnels can weaken or completely obstruct the connection.

Atmospheric Interference

As satellite signals travel toward the surface, they must pass through the Earth's atmosphere. The ionosphere and troposphere can refract or slow down the radio waves.

Since the system calculates distance based on the exact time of arrival, any delay caused by the atmosphere can result in a calculation error. The control stations monitor these atmospheric conditions and transmit correction data to help mitigate the problem, but sudden changes in solar activity or severe weather can still degrade accuracy for brief periods.

Receiver Quality and Hardware

The accuracy of a location reading often depends heavily on the device receiving the signal. A standard smartphone contains a small, inexpensive antenna and chip designed to balance performance with battery life.

These consumer devices typically offer accuracy within a range of roughly 16 feet under open skies. In contrast, professional survey equipment uses larger antennas and dual-frequency receivers to correct for atmospheric errors.

These industrial tools can achieve precision down to the centimeter or millimeter level, but they are significantly larger, more expensive, and require more power than a consumer phone can provide.

Conclusion

What began as a strategic asset for the United States Department of Defense has matured into a public resource that supports daily life across the globe. The transition from a battlefield tool to a civilian necessity demonstrates how specialized technology can have broad and lasting impacts.

We rarely think about the complex orbital mechanics occurring overhead, yet this invisible infrastructure supports everything from international banking to emergency rescue operations. It acts as a silent anchor for the modern economy to ensure that data, transport, and communication networks function in unison.

Although physical barriers and atmospheric conditions can occasionally disrupt its signals, the Global Positioning System remains the most reliable method for determining location and time. It stands as a remarkable feat of engineering that continues to guide the world with unprecedented precision.