What Is Firmware? Everything You Need to Know

You have likely stared at a screen instructing you not to power off while a “Firmware Update” progress bar slowly crawls forward. This interruption might feel frustrating, but that hidden code is actually keeping your device alive.

Firmware is a specific class of computer software that provides the low-level control for a device's specific hardware. It functions as a permanent bridge connecting physical components like chips and hard drives to the operating system you interact with.

Without it, your expensive electronics would be nothing more than paperweights.

The Technical Core: How Firmware Works

Firmware operates in the background to ensure your device functions correctly from the moment you press the power button. It provides the necessary logic that allows physical components to communicate and perform their designated tasks.

While standard applications handle complex user requests like editing a photo or browsing the web, firmware handles the mundane yet vital electrical signaling required to make those actions possible.

Low-Level Hardware Control

Firmware provides the absolute basic instructions for hardware control. It functions as the instinct of the device.

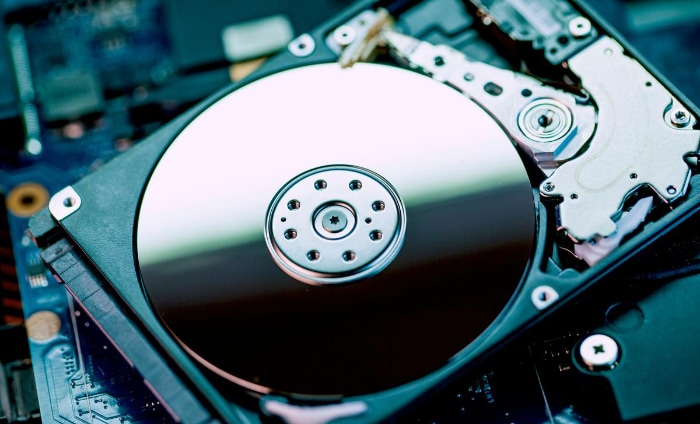

When you power on a hard drive, the operating system does not immediately know how to make the physical platters spin or how to move the read/write arm. The firmware handles these granular details.

It sends the specific electrical signals to the motor to regulate speed and positions the arm with precision. This level of control is often invisible to the user and the main operating system.

The OS simply sends a request to “read data,” and the firmware translates that high-level request into the voltage changes and mechanical movements required to retrieve it.

Storage Location and Memory

Unlike regular software which resides on your large hard drive or solid-state drive, firmware typically lives on small, specialized memory chips located directly on the device's circuit board. These are known as non-volatile memory chips, such as ROM (Read-Only Memory), EPROM (Erasable Programmable Read-Only Memory), or Flash Memory.

This distinction is vital because these chips retain their data even when the power is completely cut. If firmware were stored on the main hard drive, the computer would not be able to boot up, as it would not know how to access the drive to read the startup instructions in the first place.

The Meaning of “Firm”

The term “firmware” is an etymological middle ground between “hardware” and “software.” Hardware is “hard” because it is physical and unchangeable once manufactured; you cannot download a new graphics card.

Software is “soft” because it is easily deleted, modified, and replaced. Firmware sits in the middle.

It is code, which makes it software technically, but it is tightly coupled with the specific hardware it controls. It is not intended to be updated frequently or casually.

Because it is strictly permanent relative to a word processor but less permanent than a soldered circuit, it earns the name “firm.”

Firmware vs. Software vs. Hardware

To grasp the full function of any digital device, it helps to view it as a hierarchy of three distinct layers. Each layer relies on the one beneath it to function.

While the terms are often used interchangeably in casual conversation, the technical boundaries between the physical body, the hidden logic, and the user interface are distinct and rigid.

The Hardware Layer

Hardware represents the physical body of the technology. These are the components you can touch, hold, and break.

It includes the motherboard, the processor, the screen, the memory sticks, and the battery. Without instructions, hardware is essentially inert matter; a collection of silicon, metal, and plastic that consumes electricity but produces no result.

It provides the potential for computing power but possesses no ability to direct it on its own.

The Software Layer

Software represents the mind and personality of the device. This is the layer users interact with most frequently.

It includes the Operating System (OS) like Windows, macOS, or Android, and the applications that run on top of them, such as web browsers, video games, and spreadsheets. Software is high-level, meaning it is designed for human interaction and abstract tasks.

It is easily changeable and generic; you can run the same web browser on computers from ten different manufacturers.

Critical Distinctions

The primary difference between firmware and software lies in their relationship to the user and the hardware.

- Frequency of Change: Users update apps weekly or daily, often for minor cosmetic changes or new features. Firmware updates are rare events, usually released only to fix severe bugs or security flaws.

- User Interaction: You interact through software to get things done. You rarely interact directly with firmware. It operates autonomously. You might tweak a BIOS setting occasionally, but you do not “use” firmware to write a report.

- Dependency: This is the most significant distinction. A computer can function perfectly fine without a specific app like Spotify or Excel. However, hardware cannot function at all without firmware. If the firmware on a motherboard is corrupted, the computer will not turn on. The hardware becomes useless because it has lost the instructions that tell it how to be a computer.

Real-World Examples of Firmware Locations

Firmware is not exclusive to desktop computers or laptops. It is present in almost every device that uses electricity to process data.

From the accessories on your desk to the appliances in your kitchen, these sets of permanent instructions manage the behavior of the modern world.

Computing Devices

In the world of personal computers, the most famous example of firmware is the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System) or its modern successor, UEFI (Unified Extensible Firmware Interface). This program runs immediately when you turn on your PC.

It checks that the memory, processor, and hard drives are connected and functioning before handing control over to Windows or Linux. Beyond the motherboard, peripherals contain their own firmware.

A gaming mouse has internal code that tells it how to interpret high-speed movement and button clicks before sending that data to the computer. Even your printer relies on internal logic to translate a document into the precise movements of ink headers and paper rollers.

Consumer Electronics

Your smartphone relies on multiple layers of firmware. While Android or iOS acts as the operating system, a separate component called “baseband firmware” manages the radio hardware that connects to cellular towers.

This operates independently of the main OS to ensure you can make emergency calls even if the main system crashes. Similarly, Smart TVs utilize firmware to process incoming HDMI signals, manage color calibration, and upscale lower-resolution images.

When you press a button on a remote control, a tiny chip inside uses firmware to determine which infrared signal to blast toward the TV.

Embedded Systems and IoT

The Internet of Things (IoT) and home appliances rely heavily on firmware because they often lack a full operating system. A digital microwave, for instance, uses firmware to track the timer, monitor the door latch sensor, and control the magnetron's power level.

It does not need a complex OS to do this; it needs fast, reliable, low-level instructions. In the automotive industry, modern cars are essentially networks of computers on wheels.

Dozens of Electronic Control Units (ECUs) use firmware to manage everything from fuel injection timing and anti-lock braking systems (ABS) to the deployment of airbags during a collision. These systems must react in milliseconds, a speed that streamlined firmware provides more reliably than heavy software.

The Critical Role of Firmware Updates

Receiving a notification to update your device often feels like an inconvenience, yet these prompts represent necessary maintenance for the health of your electronics. While hardware remains static after it leaves the factory, the instructions controlling that hardware are subject to constant improvement.

Manufacturers release these updates to adapt to new threats, repair discovered errors, and ensure older devices can continue operating within modern networks. Ignoring these updates does not just mean missing out on new features; it often leaves the device vulnerable or functionally obsolete.

Security Patches and Vulnerability Fixes

The most urgent reason to update firmware is security. As hackers discover new ways to exploit hardware vulnerabilities, manufacturers must release patches to close those loopholes.

This is especially relevant for routers and Internet of Things (IoT) devices like security cameras and smart locks. These devices often act as gateways to your home network.

If the firmware on a router contains a flaw, an attacker could potentially bypass your password and access personal data. Regular updates ensure that the device has the latest defense definitions to recognize and block these intrusions.

Performance Optimization

Firmware updates can tangibly improve how a device performs without any physical modifications. Engineers often find more efficient ways for the hardware to process data after the product has launched.

By rewriting the code that manages power consumption or processor cycles, an update can extend battery life, reduce overheating, or speed up application loading times. For example, a solid-state drive (SSD) might receive an update that optimizes how it stores data, resulting in faster read and write speeds for the user.

Feature Expansion

In some cases, a firmware update can unlock capabilities that were not available when you first bought the device. This effectively provides a free upgrade.

A digital camera might gain the ability to shoot video in a higher resolution or focus faster in low light because the manufacturer improved the image processing algorithms. Similarly, high-end noise-canceling headphones often receive updates that refine the audio profile or add adjustable levels of noise suppression.

The physical speakers haven't changed, but the logic controlling them has become smarter.

Ensuring Compatibility

Technology moves fast, and devices need to adapt to communicate effectively. Compatibility updates ensure that your hardware can “talk” to newer operating systems and accessories.

For instance, when a major update for Windows or macOS is released, peripheral manufacturers often push firmware updates to keyboards, mice, and docking stations to ensure they continue working correctly. Without these updates, a perfectly good printer might suddenly fail to recognize a print job from a new laptop because it simply does not understand the newer communication protocols.

The Risks and Best Practices of Updating

While updates are beneficial, the process of installing them carries inherent risks that are quite different from updating a standard application. Because firmware operates at the lowest level of the device, a failed installation can be catastrophic.

Modifying the brain of the hardware requires precision, patience, and a stable environment.

The “Bricking” Phenomenon

The term “bricking” is used in the tech industry to describe a device that has been rendered completely useless due to a corrupted firmware installation. It turns a sophisticated piece of electronics into a paperweight or a paving brick.

This usually happens if the update process is interrupted or if the wrong file is installed. Since the firmware is responsible for the initial boot process, a corrupted version means the device cannot even turn on to let you fix the mistake.

Unlike a crashed app, which you can simply force-quit and restart, a bricked device often requires professional repair or complete replacement.

Power Stability

The most common cause of a failed update is power loss. It is vital to ensure a reliable power source before initiating any firmware installation.

If a device runs out of battery or is unplugged while it is erasing the old code and writing the new instructions, the process stops halfway. This leaves the device with incomplete logic, leaving it unable to function.

Best practices dictate that laptops should be plugged into a wall outlet, and mobile devices should have at least 50% battery charge before starting. Many modern devices will actually refuse to start an update unless these power conditions are met.

Irreversibility of Updates

Users are accustomed to the idea that if they dislike a new version of an app, they can sometimes reinstall the old one. With firmware, moving backward, known as downgrading, is often difficult, dangerous, or impossible.

Manufacturers frequently include “anti-rollback” mechanisms to prevent users from reverting to older versions, primarily for security reasons. If an update fixes a critical security flaw, the manufacturer wants to ensure the device remains secure.

This means you should read release notes carefully before confirming an update, as you will likely be committed to that version once it is installed.

Manual vs. Automatic Updates

There are two primary ways firmware is delivered: Over-the-Air (OTA) and manual installation. OTA updates are the standard for smartphones and smart home devices; the device downloads and installs the package automatically with a simple user confirmation.

This is the safest method for most people as the system verifies the file integrity automatically. Manual flashing involves downloading a file to a computer, transferring it to the device via USB, and initiating the update through a specific menu.

This method is generally reserved for advanced users, troubleshooting specific bugs, or enterprise environments where administrators need strict control over which version is running.

Conclusion

Firmware acts as the invisible soul of your hardware. It transforms a collection of cold metal and silicon into a responsive tool capable of executing complex tasks.

While the physical components provide the raw potential, it is this permanent software that directs that power and defines the device's true capabilities. Treating firmware updates with the same importance as an oil change for a car is essential for digital hygiene.

Those persistent notifications are not mere annoyances; they are critical invitations to secure your personal data and revitalize your aging equipment. Although the technical details might seem intimidating, managing these updates is a manageable aspect of modern life.

You do not need to be a computer engineer to maintain your devices; you simply need to recognize that the software inside is just as valuable as the shell around it.