What Is a Central Processing Unit (CPU)? How It Works

Every click, keystroke, and application launch begins with a command center known as the Central Processing Unit. Functioning as the brain of the machine, the CPU interprets complex instructions to turn raw data into usable action.

These silicon chips power more than just massive desktop towers; they drive the smartphones in our pockets, tablets on our desks, and even modern smart appliances. To select the right hardware or troubleshoot performance issues, users need a clear view of what happens inside this silicon socket.

Defining the CPU: Physicality and Purpose

The Central Processing Unit exists as the primary component responsible for interpreting and carrying out commands from a computer's hardware and software. It acts as the administrator for the system and dictates how data moves and processes across various components.

While often hidden beneath a cooling fan or a heat sink, this component remains the single most critical piece of hardware for general computing tasks.

Physical Form Factor

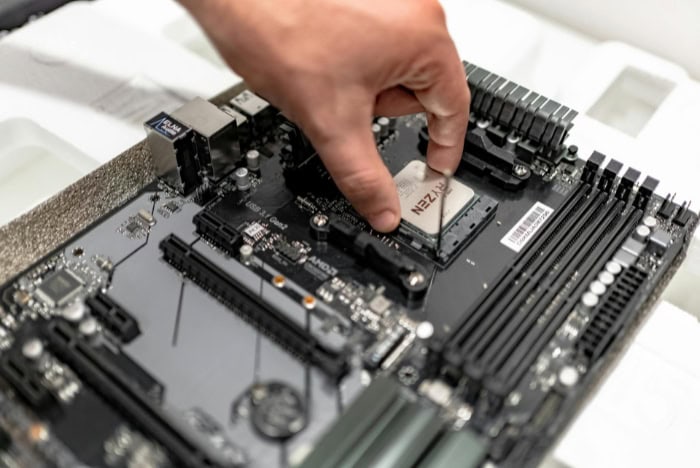

Physically, a CPU is a small, square piece of silicon known as a microchip or die. This silicon wafer contains billions of microscopic transistors which act as electrical switches.

These transistors switch on and off to represent binary code, the ones and zeros that comprise all digital data. To function, the chip sits inside a specific socket on the motherboard, secured by a latch or a mounting bracket.

The underside of the processor features hundreds of metallic contact points or pins that establish an electrical connection with the rest of the system board, allowing power to flow in and data to flow out.

Primary Function

The main role of the processor involves receiving instructions from active programs or the operating system and executing them. Every time a user opens a spreadsheet, types a document, or loads a web page, the CPU receives a specific set of requests.

It processes the raw data associated with these requests and coordinates with other hardware, such as the graphics card or hard drive, to produce the desired result on the screen. It performs these operations at incredible speeds, handling billions of calculations every second to ensure the interface remains responsive.

Architecture Basics

Processors rely on a specific architecture, which is essentially the language or set of rules the chip uses to understand instructions. The two most common architectures characterize the divide between personal computers and mobile devices.

Traditional desktops and laptops generally use x86 architecture, developed by companies like Intel and AMD. This design prioritizes high performance and complex processing capabilities.

Conversely, smartphones and tablets typically utilize ARM architecture. ARM chips prioritize power efficiency and lower heat generation, making them ideal for battery-powered devices where energy conservation matters more than raw computational force.

Anatomy of a Processor: Internal Components

A processor is not a solid block of uniform material; it consists of specialized units designed to handle different aspects of computing. These distinct sections work in unison to manage data flow, perform calculations, and store immediate information.

The efficiency of a CPU depends on how well these internal parts communicate and execute their specific duties.

The Control Unit

The Control Unit (CU) functions as the logistical manager of the processor. It does not perform calculations itself but directs the flow of data throughout the system.

You can view the CU as a traffic controller that tells data where to go and when to move. It retrieves instructions from the system memory and decodes them into signals that other parts of the computer can interpret.

The CU ensures that the right data reaches the right place at the correct time, preventing collisions or errors in the data stream.

The Arithmetic Logic Unit

While the Control Unit manages the flow, the Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) performs the actual labor. This component handles all mathematical computations, such as addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division.

Furthermore, it manages logic operations, which involve comparing numbers or data points to determine if they are equal, greater than, or less than one another. When a program requires a calculation, the Control Unit sends the necessary data to the ALU, which processes the numbers and returns the result.

Registers and Memory Management

To operate efficiently, the CPU requires immediate access to data without waiting for the slower main system memory. This is where registers and cache come into play.

Registers are extremely small but incredibly fast storage locations directly inside the CPU. They hold the specific instruction or data point currently being processed.

Supporting the registers is the cache, a hierarchy of onboard memory that bridges the gap between the ultra-fast processor and the slower RAM. Cache is organized into levels:

- L1 Cache: The smallest and fastest level, usually built directly into each core, storing the most immediately needed data.

- L2 Cache: Slightly larger but slower, holding data that might be needed soon.

- L3 Cache: The largest shared memory pool, accessible by all cores to improve general efficiency.

By predicting what data the system will need next and storing it in the cache, the processor reduces the time it spends waiting for information.

The Mechanics of Thought: The Fetch-Decode-Execute Cycle

The CPU operates in a continuous loop known as the instruction cycle. This process repeats billions of times per second, allowing the computer to run software smoothly.

This cycle ensures that instructions are handled in an orderly and predictable fashion, regardless of the complexity of the task.

Step 1: Fetch

The cycle begins with the Fetch stage. The Control Unit retrieves a program instruction from the computer's Random Access Memory (RAM).

The CPU uses a program counter to track which instruction comes next in the sequence. Once the address is located, the data travels from the RAM to the processor's registers.

This step is critical because the processor cannot act on instructions that reside solely on the hard drive; they must be loaded into the faster system memory first.

Step 2: Decode

Once the instruction arrives in the registers, the CPU enters the Decode stage. The instruction is in binary code, a string of ones and zeros that represents a specific command.

The Control Unit analyzes this raw binary data and translates it into a series of signals that the internal components of the CPU can recognize. This translation tells the processor exactly what operation to perform, such as adding two numbers or moving data to a different location.

Step 3: Execute

With the commands translated, the process moves to the Execute stage. The Control Unit sends the decoded signals to the appropriate component, usually the Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU).

The ALU performs the required operation on the data. For example, if the instruction was to add two numbers, the ALU calculates the sum.

This is the moment where the actual “processing” occurs, changing the state of the data based on the program's requirements.

Step 4: Store

The final phase is the Store stage, sometimes referred to as write-back. After the ALU completes the calculation, the result cannot simply disappear.

The CPU writes the output back into the computer's memory or keeps it in the registers for immediate use in the next instruction. This ensures the results are saved and available for subsequent steps in the software.

Once this step is complete, the program counter updates, and the CPU instantly begins the Fetch step again for the next instruction.

Cores, Clocks, and Threads

Reading a specification sheet for a processor can feel like translating a foreign language, yet these numbers define exactly how the computer will perform under pressure. Two processors might look identical physically but perform vastly differently based on their internal configuration.

To select the right component for a specific task, users must look beyond the brand name and analyze the specific metrics that dictate speed, multitasking capability, and power consumption.

Clock Speed and Frequency

Clock speed, often measured in gigahertz (GHz), acts as the most recognizable metric for CPU performance. This number indicates how many instruction cycles the processor can execute in a single second.

For instance, a CPU with a clock speed of 3.2 GHz operates at 3.2 billion cycles per second. Generally, a higher clock speed means the processor can complete tasks faster, assuming the architecture remains the same.

However, comparing clock speeds alone can be misleading if the processors are from different generations or manufacturers, as newer designs can often do more work per cycle than older ones.

Cores vs. Multi-Core Processors

In the early days of computing, processors had a single core, meaning they could process only one instruction stream at a time. They handled multitasking by switching between tasks so rapidly that it created the illusion of simultaneous work.

Modern CPUs, however, are almost exclusively multi-core. A multi-core processor contains two or more independent processing units within a single chip.

This allows for true parallel processing. A quad-core CPU, for example, can work on four distinct tasks at the exact same time.

This capability drastically improves performance in complex applications and ensures the system remains responsive even when running background processes like virus scans or system updates.

Threads and Hyper-Threading

While cores represent the physical processing units, threads act as the virtual versions of these cores. Technologies such as Hyper-Threading (Intel) or Simultaneous Multithreading (AMD) allow a single physical core to handle two separate threads of data simultaneously.

By splitting the workflow, the operating system views a single physical core as two logical processors. This allows the CPU to utilize its resources more efficiently; if one thread waits for data from memory, the core can instantly switch to processing the second thread.

This results in smoother performance during heavy multitasking, video rendering, or file compression.

Thermal Design Power

Every electronic component generates heat, and high-performance processors generate a significant amount of it. Thermal Design Power (TDP), measured in Watts, represents the maximum amount of heat a CPU generates under a typical heavy workload.

This metric serves as a guideline for selecting the appropriate cooling solution, such as a fan or liquid cooler, and the power supply unit. A CPU with a high TDP will require robust cooling to prevent overheating, which can cause the system to slow down or shut off abruptly.

Low TDP processors are generally found in laptops or silent PCs where battery life and low temperatures take precedence over raw speed.

The CPU’s Relationship with Other Hardware

A high-end processor cannot deliver peak performance in isolation. It relies heavily on the supporting hardware to function effectively.

The CPU acts as the conductor of an orchestra; even the most talented conductor will fail if the musicians cannot keep up. The relationship between the processor, memory, and graphics card determines the overall speed and stability of the computer.

The CPU-RAM Connection

Random Access Memory (RAM) serves as the workbench for the CPU. When a user runs a program, the data moves from the slow storage drive to the high-speed RAM, where the processor can access it instantly.

If the RAM is too slow or the capacity is too low, the CPU is forced to wait for data to arrive. This state, often called “starvation,” results in stuttering and lag, regardless of how fast the processor is.

High-performance CPUs require fast RAM with low latency to ensure they stay fed with data. Conversely, pairing a budget processor with extremely fast, expensive memory provides diminishing returns, as the CPU cannot process the incoming data fast enough to maximize the memory's potential.

Graphics Processing: CPU vs. GPU

For general tasks like word processing or web browsing, the CPU often handles the visual output through integrated graphics built directly into the chip. However, for 3D rendering, video editing, or gaming, a dedicated Graphics Processing Unit (GPU) becomes necessary.

The relationship between these two components is critical to avoid a bottleneck. A bottleneck occurs when one component limits the performance of the other.

For example, if a user pairs a powerful graphics card with a weak, older CPU, the graphics card will spend much of its time idle, waiting for the CPU to organize the game data. To achieve smooth performance, the capabilities of the CPU and GPU must be balanced.

Workload Suitability

Selecting the right processor involves matching the specifications to the intended use case. Different workloads stress the CPU in different ways.

Gaming, for instance, typically favors higher clock speeds and strong single-core performance, as many game engines still rely heavily on a primary thread. In contrast, creative professional tasks like 4K video editing, 3D modelling, or compiling code benefit more from a high number of cores and threads, even if the individual clock speed is slightly lower.

Identifying the primary purpose of the machine ensures that money is spent on the features that actually impact the user's daily experience.

Conclusion

The Central Processing Unit stands as the undeniable definition of computing power, functioning simultaneously as a rigorous manager and a relentless calculator. Through the Control Unit, it directs the chaotic traffic of data to ensure every command reaches its destination without error.

Concurrently, the Arithmetic Logic Unit handles the heavy lifting of mathematics and logic by executing the calculations that drive software applications. This dual nature allows the machine to remain both organized and powerful, balancing the need for complex management with the demand for raw speed.

As technology progresses, the concept of performance has moved beyond simple frequency increases. While the industry continues to push the boundaries of transistor density, often cited in relation to Moore's Law, modern gains rely just as much on intelligent design as they do on microscopic shrinkage.

The focus has shifted toward smarter architecture by utilizing efficient multi-core layouts and larger memory caches to handle parallel tasks. A processor is no longer judged solely by its clock speed but by its ability to work smarter, manage heat, and coordinate seamlessly with the rest of the system hardware to deliver a responsive experience.